ASML: The Invisible Monarch Holding the Tech World Hostage.

400 million dollars, 220,000 degrees, and absolute monopoly: Meet the gatekeeper of the digital age.

Imagine for a moment that the oxygen required for the global economy to breathe was produced by a single factory, located in a small European town that almost no one can name. If that factory closes, the world suffocates. This dystopian sci-fi scenario is actually the exact reality of the modern technology industry.

The factory doesn’t produce oxygen, but something that has become just as vital for our digital civilization: the ability to manufacture the brains of our machines.

This company is called ASML (Advanced Semiconductor Materials Lithography). Based in Veldhoven, in the Netherlands, it is the sole guardian of a technology so complex it borders on black magic. Without it, Apple releases no new iPhones. NVIDIA produces no chips for Artificial Intelligence. Google and Amazon’s data centers slowly fade to black. Next-generation missiles don’t fly.

This is the story of the most complex machine humanity has ever built, and of the Dutch firm that literally has the global tech industry—and by extension, the global economy—by the balls.

The Awakening of the Silicon Dragon: Inside the Belly of China’s “Manhattan Project”.

How Beijing’s secret quest for the technological “atomic bomb” is shattering Western supremacy and redrawing the global order.

I. 400 Million Dollars: The Price of Exception

In the world of “High Tech,” we are used to astronomical numbers. But here, the scale shifts entirely. The star of the ASML catalog is the EUV Lithography machine (Extreme Ultraviolet).

The sticker price? Roughly 350 to 400 million dollars. For a single machine.

And this isn’t the kind of equipment you order on Amazon Prime. Each machine is the size of a double-decker bus, weighs 180 tons, and requires three entire Boeing 747 cargo planes to be delivered in pieces. Once it arrives at the client’s site (like TSMC in Taiwan, Intel in the US, or Samsung in Korea), it takes months of assembly and a team of hundreds of ultra-specialized engineers to calibrate it.

Why such a monopoly?

The legitimate question is: why doesn’t anyone else do it? Canon and Nikon, the giants of Japanese optics, used to manufacture lithography machines. But when the industry had to break the technological sound barrier to transition to EUV, they looked at the specifications, took out their calculators, and gave up. It was considered physically impossible and economically suicidal.

ASML stayed. They bet their entire existence on a technology that everyone said was unachievable. Today, they possess 100% of the EUV lithography market. 100%. It is the purest and most terrifying monopoly in modern industrial history.

II. Into the Matrix: Creating a Sun on Earth

To understand why these machines cost the GDP of a small nation, you have to dive into their entrails. The goal is to etch circuits onto a silicon chip. To etch smaller, you need light with a shorter wavelength.

For years, we used standard ultraviolet light (DUV). But to get below 7 nanometers (the size of current transistors), we had to switch to Extreme Ultraviolet (EUV), with a wavelength of 13.5 nanometers.

The problem? This light does not exist naturally on Earth. It is absorbed by everything: air, glass, and any standard lens. To generate it, ASML had to reinvent physics.

The infernal dance of tin

Here is the process, and it is barely believable:

The Droplet Generator: The machine propels microscopic droplets of molten tin (the size of a white blood cell) into a vacuum chamber.

The Speed: These droplets travel at roughly 250 km/h (155 mph).

The Laser Shot: An ultra-powerful CO2 laser (developed by the German company Trumpf) targets these moving objects. But it doesn’t shoot just once.

The first shot (Pre-pulse): It hits the droplet just hard enough to flatten it, turning it into a pancake shape to increase its surface area.

The second shot (Main-pulse): A fraction of a second later, a main shot pulverizes the tin “pancake.”

The Explosion: The tin is instantly vaporized into plasma.

This is where the numbers go crazy. This plasma reaches a temperature of 220,000 Kelvin.

Note this well: 220,000 Kelvin is about 40 times hotter than the surface of the Sun.

ASML doesn’t just do this once in a while. The machine repeats this process 50,000 times per second.

50,000 droplets. 100,000 to 150,000 laser shots. Every second. 24 hours a day.

And as the engineers in Veldhoven proudly say: “We don’t miss.” They never miss. Missing a droplet means risking damage to optics worth tens of millions of euros.

It is the equivalent of shooting an arrow from Earth to hit a coin on the Moon, while riding a merry-go-round... and succeeding 50,000 times in a row without blinking.

III. The Smoothest Mirrors in the Universe

Since EUV light is absorbed by glass, you cannot use lenses to focus it. You need mirrors. But not just any mirrors.

This is where ASML’s historic partner comes in: Carl Zeiss, in Germany.

These mirrors are marvels of multi-layer engineering. They are composed of dozens of alternating layers of silicon and molybdenum, each only a few atoms thick, designed to reflect this incredibly finicky light. But it is their polishing that defies imagination.

The Earth analogy

To illustrate the perfection of these mirrors, let’s use a famous comparison:

If you blew up a Zeiss EUV mirror to the size of the planet Earth, the highest mountain or the largest bump on its surface would be thinner than a playing card.

These mirrors must guide the EUV light (invisible to the naked eye) through the machine to project the processor blueprint onto the silicon wafer.

The precision required to overlay the different layers of the processor is in the order of a few nanometers (about 5 atoms wide).

Imagine having to draw a complete city map on a grain of rice, with a pen that shakes, while riding a train moving at full speed. To compensate for vibrations, the wafer stage (the table holding the chip) levitates using magnets and moves with an acceleration of more than 20 G. That’s faster than a missile at takeoff, yet it stops with nanometric precision.

IV. The History: The Ugly Duckling Becomes a Swan

The most ironic thing about this global domination is ASML’s origin story.

In 1984, Philips (the Dutch electronics giant) and ASM International created a joint venture. They called it ASML. At the beginning, it was a disaster. They were set up in “leaky sheds” behind Philips’ buildings in Eindhoven. No one believed in them. The machines didn’t work, money was tight, and employees had to bring their own coffee because the coffee machine was broken.

During the 90s and 2000s, the competition was fierce. Nikon and Canon dominated the market. But ASML made a radical strategic decision: modular architecture and open research. Instead of doing everything themselves, they partnered with the best in the world for each component (Zeiss for optics, Cymer for lasers, etc.).

But the real turning point was the gamble on EUV.

For over 15 years, EUV was the industry’s “running gag.” People said, “EUV is the technology of the future, and it always will be.” It was too hard. Too expensive. Unstable.

The Americans threw in the towel. The Japanese threw in the towel.

ASML kept going. They burned billions in R&D. They convinced their own customers (Intel, Samsung, TSMC) to invest in the company to fund the research. And around 2018-2019, the miracle happened: they managed to reach mass production.

Overnight, they became untouchable.

V. A Massive Geopolitical Weapon

Today, ASML is no longer just a tech company. It is a major pawn on the global geopolitical chessboard.

Since ASML is the sole source of these machines, whoever controls ASML controls the technological future. This is why the US government has exerted immense pressure on the Netherlands to ban the export of EUV machines to China.

If China wants to develop its own 5nm or 3nm chips for its AI and military, it needs ASML’s machines. But ASML is not allowed to sell to them. It is a total technological embargo.

Beijing is furious, but powerless in the short term. Recreating a supply chain capable of building an EUV machine would take decades. It’s not just a matter of stealing the blueprints.

The complexity of the Supply Chain

An ASML machine contains over 100,000 ultra-complex components.

The lasers come from San Diego or Germany.

The optics come from Germany.

The chemicals come from Japan.

The sensors come from the USA.

If a single link in this global chain breaks, the machine cannot be built. This is what makes copying by China so difficult: you don’t just have to copy ASML; you have to copy Zeiss, Trumpf, Cymer, and hundreds of other cutting-edge suppliers.

There are even rumors of a software “Kill Switch” integrated into the machines, allowing ASML to disable them remotely if they ever fell into the wrong hands during a military invasion (for example, in Taiwan). True or false? The mere fact that the rumor exists highlights the critical level of the stakes.

VI. The Future: Further, Faster, More Expensive

ASML is not resting on its laurels. While the world is still trying to figure out how they pulled off EUV, they are already deploying the next generation: High-NA EUV.

These new machines (TWINSCAN EXE:5000 and beyond) are even bigger, even more precise, and will allow for the etching of chips at 2 nanometers and below. The price? We are talking about 380 to 400 million euros per unit, potentially more. Intel has already received the first one.

The race for miniaturization continues, and ASML is the only driver in the car.

The vulnerability of the system

However, this situation is terrifying. The entire global economy rests on the stability of a single company, in a single region of Europe. A fire, an act of sabotage, or a natural disaster in Veldhoven, and the global production of cutting-edge chips stops dead. No new servers, no smartphones, no autonomous cars.

It is the paradox of our era: we have built a digital civilization of infinite complexity, which rests on a shockingly narrow base. An inverted pyramid balancing on the tip of a tin droplet heated to 220,000 degrees.

Final Thoughts: The Art of the Impossible

ASML’s story is a lesson in humility and ambition. It reminds us that behind the fluid touchscreens and the artificial intelligences writing poetry, there is “hard tech.” Real, heavy, dirty, loud, and incredibly precise engineering.

To say that ASML “holds the world by the balls” is a crude image, but it is frighteningly accurate. They are the guardians of the temple. As long as their lasers hit those droplets of tin without ever missing their target, the digital world keeps turning.

The next time you look at your smartphone, spare a thought for those Dutch engineers who, somewhere in a silent cleanroom, are creating little suns on Earth, 50,000 times a second, just so you can scroll through your feed.

It is completely crazy. It is terrifying. And it is absolutely magnificent.

The Real Stablecoin: Why Bitcoin Is the Only True Anchor, While USDT Sinks.

True stability isn’t a fixed price; it’s fixed supply. Why holding “stable” tokens is a guaranteed loss, and why Bitcoin is the only lifeboat that floats.

The War Is Over: Why NVIDIA's $20 Billion "Non-Acquisition" of Groq Just Ended the Inference Race.

While the world was busy counting H100 stockpiles and analyzing the supply chain of CoWoS packaging, the war for the future of Artificial Intelligence ended. It didn’t end with a bang, or a regulatory investigation, or a flashy press conference in a leather jacket.

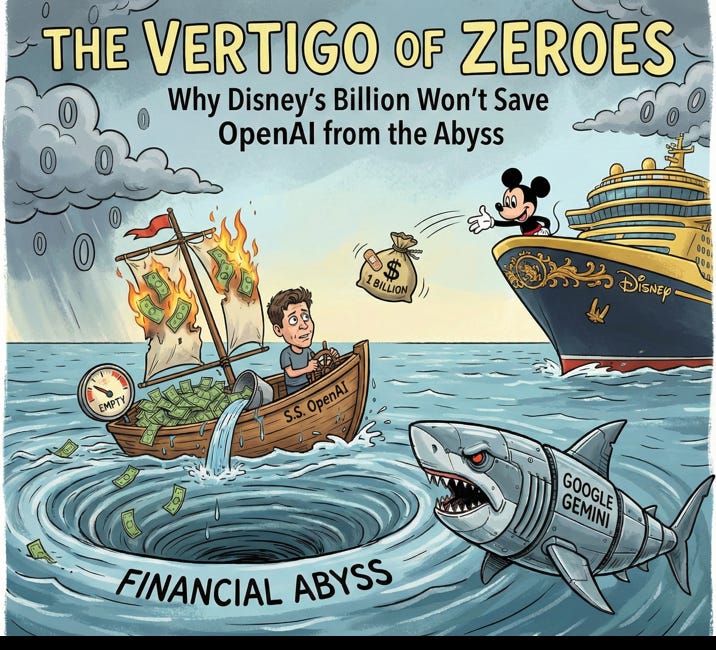

The Vertigo of Zeroes – Why Disney's Billion Won't Save OpenAI from the Abyss.

It is news that sent tremors through Silicon Valley and delighted Wall Street: OpenAI, the creator of the revolutionary ChatGPT, has just sealed a Faustian bargain with the enchanted kingdom of Disney. On paper, the deal is glittering. It promises the integration of pop culture legends—from Mickey Mouse to Star Wars Jedi—into Sora, OpenAI’s hyper-realis…